by Mark Tracy

Why do same-sized objects that are farther away appear smaller? Is it a consequence of the laws of physics, or is it an accident of my perceptual processing? Or is it impossible for me to know either way?

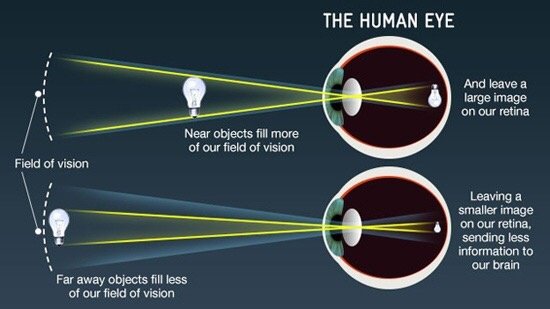

A naive response is that farther objects appear smaller because the light traveling from an object to the retina forms a cone, and farther objects subtend a lesser angle on the retina. This standard response is illustrated in the diagram below, which can be found on Quora, here (in a response to this post—I have no other sourcing information).

However, it seems that I could conceivably experience that same raw data of the photons subtending a lesser angle in my retina’s receptive field as being objects of equal size but a different clarity, or some other distinction. In other words, an alien perception could operate and subjectively appear entirely differently. So in some sense, this particular appearance of order is an accident of my perceptual processing.

Even more strongly, the question itself only has meaning at all through the semiotics of my consciousness. For the reader who may not be familiar with this language, “semiotics” is the study of symbols and meaning-making. I’ll next introduce some basic notions about symbols in order to clarify what I mean by “the semiotics of my consciousness.”

A “symbol” as I mean it is composed of two interacting sub-parts: there is the signifier, such as a word (e.g. “arm”), and the signified, which is the actual physical process or processes referred to by the signifier (e.g. my actual arm). More generally, without adopting the language of physicalism, we might consider the signified to be a collection of imaginations, or mental experiences, such as I would experience from viewing or imagining my arm. The meaning of the signifier—that is, the map from signifier to imaginations or real processes—is given by a particular brain or mind. What I mean, then, by “the semiotics of my consciousness” is how I lend meaning to symbols, such as “my arm.”

Let’s dive even further into the example of “my arm.” To me, “my arm” refers to everything from the shoulder to the tips of the fingers. First, note that the description I have just given requires knowledge of the meaning of a series of other symbols, such as “shoulder,” “fingers,” as well as an intuitive understanding of the “from-to” relation. Second, one can easily imagine that to another person, “arm” could mean everything from the shoulder to the wrist, but not including the hand. This example illustrates how every symbol is embedded within a system of symbols, and meaning is assigned to them by a particular mind or brain.

Now, what does it mean that the question of why same-sized objects that are farther away appear smaller “only has meaning at all through the semiotics of my consciousness”? Well, for an object to be “farther” than another object at all refers to a third reference point to which one object is closer and the other farther, and to “appear smaller” necessitates a consciousness at that reference point to whom it appears at all. Finally, and significantly, it assumes the notion of an “object” that is in some sense stable and unified enough to be identifiable as one “thing” across time. So this question only makes sense through the semiotic lens of a consciousness that exists at a point or in a limited region of spacetime upon which stable-enough patterns in physical processes can impinge to impart abstract, object-oriented information.

Though we may now be tempted to say that the apparent fact that same-sized objects that are farther away appear smaller is an accident of perceptual processing, we must also acknowledge that our perceptual processing may itself be a consequence of the “true” laws of physics, or divine Logos, if such exists. For example, it could be that such perception is inevitable, given the reality of some general form of the theory of evolution by natural selection and the survival advantage of such an encoding of information (for example, that it allows us to recognize important spatial information about physical reality).

So then we are led to the conclusion that we cannot possibly know either way whether the apparent fact in question is due to the laws of physics or is an accident of our perceptual processing. The two are irrevocably linked through semiosis, the meaning-making process, itself.

Considering all of this, it seems to me that physics tells us how things go on; but not what goes on. “What goes on” is dependent on consciousness, on abstract, semiotic systems mapping that which in the language of physics may be called “spatiotemporal process” to symbols, or object-oriented, timeless representations.

In other words, to “be something” is to “be-something-to.” Physics may tell me how my arm moves, but never what “I” am or what “my arm” is, because those notions are situated within a semiotic system. “My arm” does not physically exist as such. It exists as “arm” only “semiotically,” with its meaning mediated by my consciousness.

This is of course not to say that physics is not helpful or useful—not at all—but it follows that there is not necessarily ontological privilege for the fundamental “objects” identified by physics. They also can be said to exist as such only semiotically.

Our perceptual experience is always already imbued with meaning—it is not a “raw” or “neutral” input that we then interpret, but comes to us pre-interpreted through learned categories and distinctions. The visual experience of size and distance is one example of this: we don’t just passively receive retinal images, but actively construct a meaningful, three-dimensional world of objects located in space.

This meaning-ladenness goes beyond specifically human modes of perception. The broader point is that any organism’s Umwelt or “lived world” is constituted through its particular ways of making meaning, its semiotic systems. For a bat, the world is primarily a soundscape of ultrasonic reflections; for a dog, a richly textured smellscape; for an electric fish, a field of electrical gradients.

Each organism inhabits a world of significance that is co-constructed through its embodied interactions and evolutionary history. There is no “view from nowhere,” no Archimedean point outside of semiosis from which to grasp “things in themselves.”

The human case is perhaps special in the degree to which our semiotic systems are flexible, open-ended, and mediated by language and culture. But the basic principle of the semiotic constitution of lived worlds applies across the board. Meaning and being are always entangled: ontology is always bound up with semiosis.

Leave a comment